The first developed social psychology theories of power took the approach that power could only be understood within a social field (Lewin, 1951), meaning among people who’s social distance was directly (and inversely) related to how much power—social influence—they had over each other. In fact, the analogy Kurt Lewin used to describe a “social field” is that of a “force field.” (Lewin originally was pronounced “Levine” because it is a German name, but he Americanized it—Kurt Lewin was a German Jewish refugee to the U.S. pre-World War II, one of many Jewish European scientist who was very important in developing science in the U.S.)

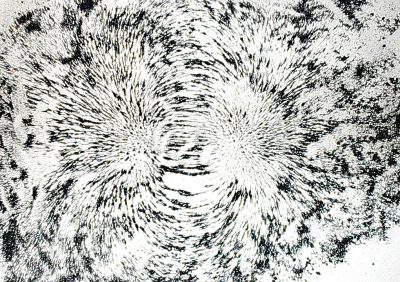

The force field analogy may help describe human power.

Imagine that there are several magnets fixed by glue on a board at varying distances to each other under a sheet of paper. If you sprinkled iron filings on the paper, you would see the filings array themselves in response to the magnetic fields produced by magnets. Bigger magnets would influence filings father away than smaller magnets. With multiple magnets, one would not get a simple pattern as one does with one magnet—the filings would be subject to the magnetic force of every magnet, but be influenced by them depending on magnetic strength and distance from the magnet. The pattern of the filings shows the strength of potential influence of each magnet to the others.

Now, suppose we unglue the magnets. Then they would actually move in response to the magnetic fields of each other and whether they attract or repel each other. The filings would of course rearrange to follow the motion of the set of magnets, and there is no guarantee that the magnets would ever settle down to rest in the near future, especially if we perturbed the system by passing other magnets by or through the array. (A gravitational field with different sizes bodies also works, perhaps better, for this analogy, but you have to imagine the force field that iron filings illustrate).

The points Lewin wanted to communicate about human power are that 1) power is relational, but how much power is possible between any two persons depends on how much one is in the other’s orbit, 2) power is fluid – so it is not a fixed property of a person like an authority role might be, and any given power relation can always change, 3) power is not just a matter of two individuals or other parties.

Lewin made another point that helps show just how complex power is—and this one is psychological: that people are not just passively reactive to each other (unlike magnets). Instead, people often consider the possible consequences of their actions on how others might behave, and then what that would mean for themselves and others. We sometimes don’t think before we act, but it is surely in one’s habits to consider how a friend (or enemy) might react to a remark, and whether that will produce behavior from that other, and others still, that one would like. (Once you believe you have to behave in a particular way in order to get cookies made for you, you can decide whether you want to do so, or whether it isn’t worth it to you to be manipulated or whether the cookies are not worth the effort, or you don’t like what it would mean to someone other than the cookie-maker if you appear to want to please her, or what.) So trying to predict what other people will do is an essential process to power dynamics—that’s the social psychology. This means that power is really a potential thing.

Measuring possibilities is not easy. (See The In Game Method).